Humans work in groups all the time. Indeed, I argue we are stronger because of it. Specialization and trade allows for a team to achieve things no individual could accomplish on their own. Economists since Adam Smith have highlighted the group efforts needed to produce even simple things such as wool coats, pencils, and bread. Indeed, liberals have long celebrated the ability for people to cooperate without explicit coordination!

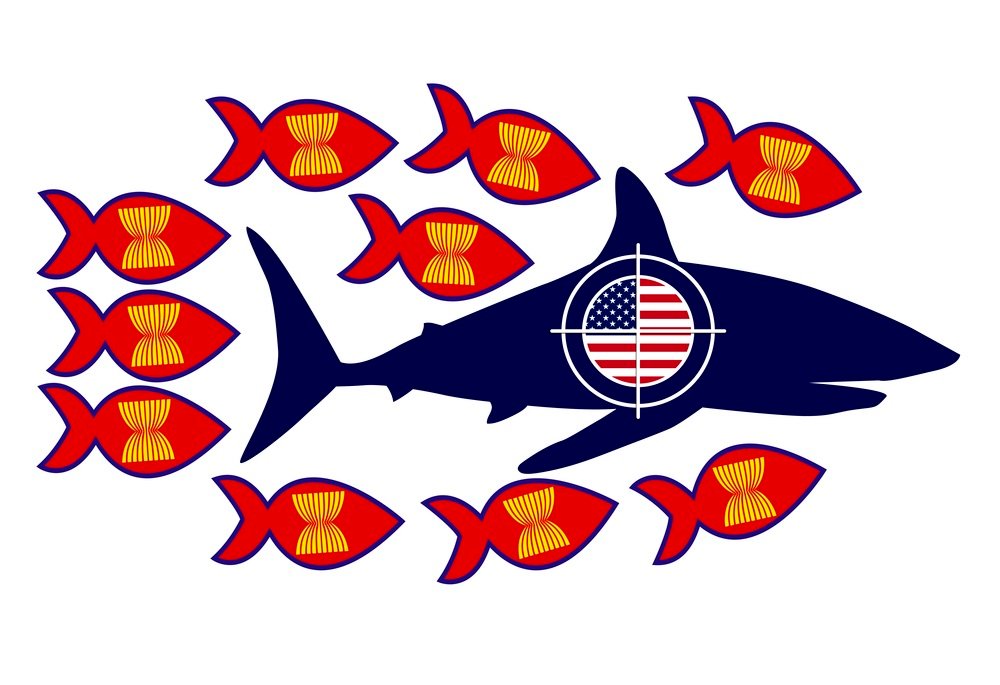

However, these collectives sometimes get blended together. What is good for one group is often asserted to be good for another. Or that there is some overarching group, and all other groups are subsumed into that group. Again, what is good for that overarching group is asserted to be good for all its parts. We see this particularly in international trade, and with protectionism in particular. Protectionism is rife with this fallacy of composition- in particular, the national defense justification for tariffs.

I have written a lot on the national defense justification for tariff. This 2018 piece from me here at Econlog remains one of my favorites. I am working on a book with Don Boudreaux on international trade where we expand upon national defense justifications. The essential idea is there is some good necessary for national defense, procuring it from a foreign source has a high risk of disruption, and therefore tariffs are required to attempt to develop the industry domestically.

Theory often departs from reality, however, and there is mounting evidence that national defense tariffs actually weaken national defense capabilities (for example, see Colin Grabow and Inu Manak’s The Case Against the Jones Act or Mancur Olson’s The Economics of the Wartime Shortage).

But the argument for tariffs on military goods, at least how it is currently deployed, rests on a confusion about collectives. Let us suppose that national defense tariffs are:

- Necessary,

- Easily targeted

- Not prone to rent-seeking, political manipulation, or other forms of corruption

In short, let us assume national defense tariffs work perfectly as intended. It does not logically follow, however, that those national defense tariffs would be the best, or even a good, way to achieve their intended goals. Tariffs, recall, apply to all users of a particular input, not just one. Firms that use, say, microchips for their products must also pay higher prices for their inputs.

Justification for national defense tariffs is presented as “we” want a domestic source of the good. But that is not the case. The government wants it. But most of us do not. Why force others to pay a higher price when only one group needs it? The government can buy from domestic suppliers. There is no need to force everyone else to as well.

In other words, we need to think of “The United States of America” not as a single collective entity represented entirely by the wishes and desires of the Federal Government, but rather as a collection of various groups, each with their own individual wishes and desires, and their own agency. The Federal Government is not the representative of Americans. It is a unique corporation with a specific purpose. It may conduct its business as it sees fit. But what is desirable for the government is not necessarily desirable for the people living under the government (and vice versa).

Collectivist ideologies have many problems. One of the biggest is they ignore the complexities of society by subsuming everything under a broad umbrella and is coterminous with the government. This, in turn, leads to many disastrous policy mistakes, such as protectionism.

Jon Murphy is an assistant professor of economics at Nicholls State University.